Judge Turpin's "Johanna"

What Turpin's mea culpa reveals, and what disappears without it

Mark Eden Horowitz, during his landmark 1997 series of conversations with Sondheim, asked about a recurring habit in productions of Sweeney Todd: the cutting of Judge Turpin’s “Johanna.”

MH: You feel strongly that it should be kept in the show.

SS: Yes—he’s the only character who’s not musicalized. If this song isn’t in the show, he doesn’t have anything to sing that is his alone.

Sondheim’s response points us to something structural about how musical theatre makes meaning. A character who only ever sings alongside others can remain, in a particular way, untested. He can stay in posture. He can keep his mask on. Without “Johanna,” we experience the Judge chiefly in two modes: public authority (law, household, status) and interpersonal pressure (Johanna cornered, Anthony dismissed, the Beadle enlisted). We understand him, certainly. But we don’t necessarily hear him.

Thank you for reading! Upgrade to a premium subscription for full access to The Sondheim Hub: an exclusive essay, crossword, extended interview & more each week, plus our complete, paywall-free library of 250+ essays, features & interviews.

If the only sustained musical window we have into Turpin is the shared, elegant “Pretty Women,” we risk misreading the kind of villain he is. We can take him for a conventional hypocrite: corrupt, yes; predatory, yes; but essentially stable. A man who does what he does from a position of assurance.

His “Johanna” says: no. This man is compulsive, not stable. It’s not so much that he’s hiding sin as it is that he’s staging it for himself, again and again, in the same room, with the same props. He is a self-directed melodrama.

That matters, because Sweeney Todd is a show that lives and breathes private ritual. Think of Todd’s intimate, devotional communion with his razor. Think too of Johanna: her birds, her window, her daily rehearsal of a freedom she can’t yet claim. Anthony, pacing Kearney’s Lane, daring to look up, repeats his own small ceremony of hope. Even the Beadle steadies himself through ritual: his cozy moral cant, and later those parlor songs, rehearsed like hymns to himself. Judge Turpin’s “Johanna” is the most naked version of this pattern: a private ritual of guilt and desire staged without mitigation, and therefore impossible to ignore.

Turpin, then, deserves the same treatment—not to “round him out,” and certainly not to soften him, but to make his corruption legible in the show’s own language.

Looking back at Christopher Bond’s play makes the function of Turpin’s “Johanna” feel even clearer.

Bond gives Turpin a set-piece confession before Johanna enters. The stage directions are blunt: the Judge arrives in his robes with a scourge in one hand and an open Bible in the other. He reads, “Let him who is without guilt cast the first stone,” then turns the verse into self-indictment:

I, who by my office should be incorruptible, have ripped the blindfolds from sweet Justice’s face, and stained her blameless sword with innocent blood.

Then the language slides, as if on greased rails, into erotic disgust:

Now, teeming flesh, take thou the recompense. […] And all for loathed lust! Out, out! Vile bestial man! Lascivious devil, down!

He falls to his knees, sobbing. He speaks of “a cankered weed” that “entwined itself around that sweet flower of father feeling.” “That weed is lust,” he says, “and now it chokes my soul.” He then lashes himself “into a frenzy, moaning and shrieking,” before he resolves to wed Johanna, determining himself incapable of change.

Bond’s Judge shows us contradiction as a practice. Turpin confesses in order to continue, not to change—and the confession itself seems to become part of the appetite.

In Sondheim’s hands, Turpin’s confession becomes a number that is at once more stylized and more revealing. Where Bond’s Judge begins by invoking scripture, casting himself in the biblical language of sin and judgment, Sondheim’s Judge begins instead with liturgy. His first words are Latin:

Mea culpa, mea culpa,

Mea maxima culpa,

Mea maxima maxima culpa!

It’s the language of ritualized self-accusation; not a verse to be interpreted, but a formula designed to be repeated. Drawn from the Catholic Confiteor, the phrase carries centuries of mechanical penitence with it. Turpin continues:

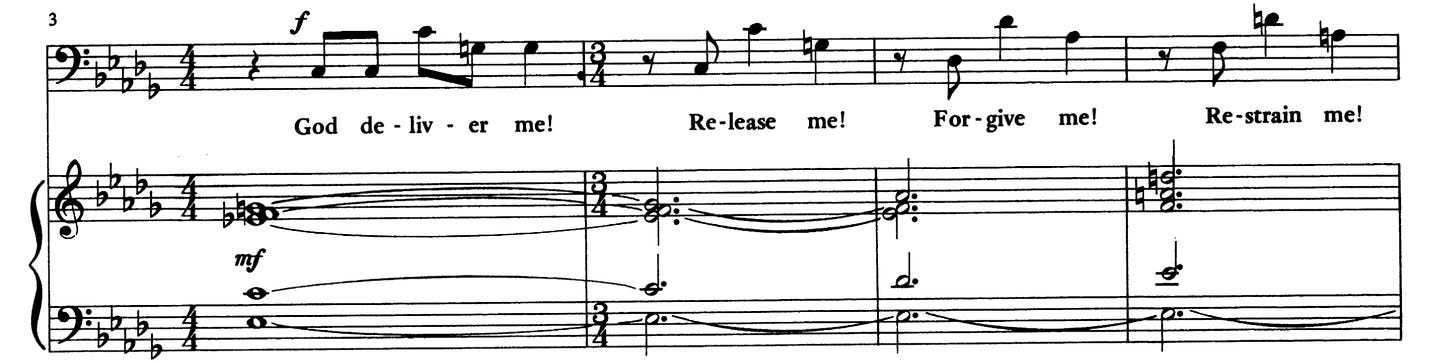

God deliver me! Release me!

Forgive me! Restrain me! Pervade me!

“Restrain me” is moral. “Pervade me” isn’t. Or rather, it’s moral in the way Turpin has made morality useful: as a language that can be erotically charged while pretending to be pure.

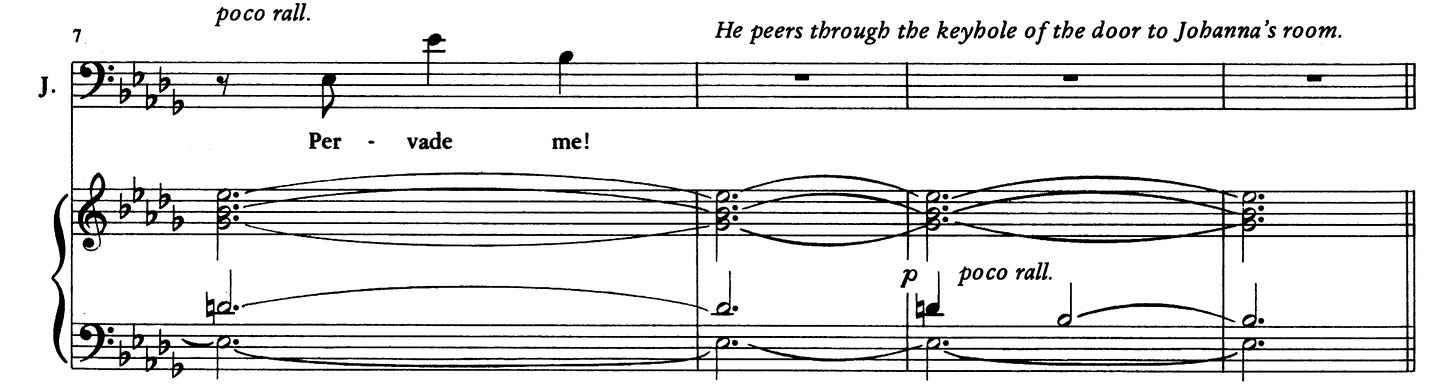

Sondheim underlines that slippage musically. The highest note of each plea, from “Release me!” on, inches upward in pitch from C—forgive a half-step higher, restrain higher still—until pervade crowns the phrase, reaching the highest note yet (E♭). The music creeps up where the language pretends to kneel.

Sondheim told Horowitz that Hal Prince worried this song would offend—misread, perhaps, as masochistic self-flagellation played for sensation. Sondheim’s own defence is essentially contextual: in Victorian terms, for this man, the mixture of lechery and guilt is in fact the rotten core of a particular kind of respectability.

And in peering at Johanna through her keyhole, Turpin shows us he can’t even perform penitence without glancing back at the source of his lust. That’s the point: his “repentance” is a technique for looking again.

Sondheim also admitted, in that Horowitz exchange, that early previews revealed a “longeur” in the middle of Act I: the show spends a stretch of time away from Todd and Mrs. Lovett, moving through Johanna/Anthony material, the town square, Pirelli, and the Judge’s chambers. Something had to go, and “Johanna” was one of the first casualties.

That’s the pragmatic case against this number, and there’s certainly logic to it. Sweeney Todd is a show with a central gravitational pair; the further we drift, the more we feel their absence.

So why does “Johanna” often work better once the show “finds its shape,” as Sondheim put it? Why can it be reinstated without breaking the tension?

Partly because the song does two jobs at once:

It gives us the Judge’s private engine, without which he risks becoming merely functional plot machinery.

It clarifies the entire Johanna subplot’s moral stakes by revealing the logic that sustains her enclosure. The sealed household is no longer just a fact of her life, but the solution Turpin has devised for his own desire.

In other words: the number makes the detour part of the main story, not a diversion from it. It shows that Turpin operates by the same moral logic as Todd, shaped by the same city and its permissions.

If you cut “Johanna,” you save time. You might reduce a feeling of drift. You avoid staging a moment some people find uncomfortable. But you also remove the mechanism that makes Turpin legible. Without it, he risks becoming efficient rather than revealing, a functionary of menace rather than a man governed by ritual. The sealed household remains, but its logic goes unexplained.

You also lose something Sweeney Todd does nowhere else so nakedly: the collision of sex, religion, and authority in a single, unmediated act of self-performance. And you lose a piece of musical dramaturgy Sondheim cared about deeply: the insistence that every major figure in this plot-heavy score must be allowed one moment alone with their governing fiction.

Most of all, you lose the particular theatrical irony the song crystallizes. The Judge believes his virtue survives because he punishes himself for desiring. But the punishment is part of the desire, and his mea culpa is choreography to that end.

What Turpin’s “Johanna” reveals is not that he feels guilty, but that guilt is part of the form his desire takes. Cut the number, and that logic disappears. Keep it, and the show tells the truth.

Beneath Turpin’s self-punishment lies a system — of confession, purity, surveillance, and authority — that gives his desire its shape. In this week’s paid-subscriber essay, we’ll trace that system in detail. We’ll explore how “Johanna” turns private corruption into a kind of theatre, with the audience cast as its silent witness. If you’d like to support our work and receive every paid-subscriber essay, simply click below.

✍️ Please support our work by upgrading to a premium subscription:

The Sondheim Hub exists solely thanks to the generous support of our readers. Please consider supporting our work for a few dollars each month. A premium subscription gives you full access to The Sondheim Hub: an exclusive essay, crossword, extended interview & more each week, plus our complete, paywall-free library of 250+ essays, features & interviews. 📚

Great article. I admit, I was really surprised that the last Broadway revival didn't include this song.

Hal Prince himself claimed that he just never found a way to stage the Judge's Johanna that made him happy, although I suspect Sondheim is right that he also felt it made the audience too uncomfortable. I've yet to find any images or footage of how Prince did stage it in previews, but interestingly when he restaged Sweeney for Houston Grand Opera and New York City Opera in the 1980s, in productions based closely on the designs and staging of the original Broadway, he DID put the number back in. And yet again, I've never come across footage of how he staged it, but apparently he found a way that made him happy (the Houston production was broadcast live--but on radio only.)

And I really need to do my research better, but wasn't the song placed in a slightly different place on the original Broadway cast album than it would be on stage?

Spot on. The private ritual lens is so integral. Really a great breakdown. Thanks!